Introduction

The purpose of this article is to be able to evaluate an individual’s mobility in their ankles using the tools we have available to specifically the use of the Messier squat in the evaluation process. The Messier squat is a unique closed-chain movement where an athlete brings their hips down and shifts from side to side, targeting the tissue of the lower body in the frontal plane.

Video: Example of a bodyweight messier squat

Before getting into the use of the Messier squat in an athlete evaluation, we can first discuss a holistic approach to a lower body evaluation. It has become fairly common knowledge that issues at the knee can be caused by other areas of the body most commonly the ankle and the hip.

Image: Athletes performing a barbell overhead squat

When approaching an evaluation, I start with the Overhead Squat to guide my direction. When doing an overhead squat, if an individual has an excessive forward lean in the torso, heels coming up or foot flattening, turning out, then those are indicators that the lower leg may be responsible for the dysfunction showing up in the squat. These issues can be observed in other weight room instances as well, especially under higher loads. On any squat pattern, these types of issues can be observed in the ankle/foot. If an athlete is doing a moderately heavy squat, then you may notice feet flatten or an excessive forward lead at the torso or a small amount of heels rising off the ground. I have also noticed feet flattening on trap bar deadlifts. If you work with a high volume of athletes and don’t have time to perform a baseline movement assessment and plan on incorporating some kind of squatting pattern in their training, then this could be a tool for understanding if they have any lower body movement patterns that call for further screening. If the athlete is showing a lack of ability to find the positions after providing cues on a traditional squat pattern, I would be willing to bet that the same issues will show up in a much more significant way during an overhead squat assessment and likely more so when screening the individual joints in question. The quick way to confirm the analysis is to block off/elevate the individuals’ heels. If elevating the heel clears up the movement issues, then you can be fairly certain the dysfunction is being created by the lower leg.

Image: Comparison of an athlete squatting with and without the heels elevated to compare knee valgus – source: Bell, D. R., Oates, D. C., Clark, M. A., & Padua, D. A. (2013). Two-and 3-dimensional knee valgus are reduced after an exercise intervention in young adults with demonstrable valgus during squatting. Journal of athletic training,48(4), 442-449

An evaluation can and probably should include a mobility test for ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion and inversion and eversion. These will likely show up as a lack of range of motion and can be a good indicator of what tissue should be addressed. It is worth screening the knee for flexion and extension and screening the hip for flexion, extension, internal rotation and external rotation as a precaution and to understand the individual’s biomechanics.

An evaluation can and probably should include a mobility test for ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion and inversion and eversion, says @Graham Sokol

Share on X

Using Pain as an Indicator

Using pain in joints can be viewed as an indicator of what tissue should be addressed or what biomechanical movement is causing the pain. If a person has pain in the ankle or the knee that has gone unidentified by PT, AT, or the Coach’s previous evaluations, then these can be used as tools to understand the individual circumstances and make adjustments based on findings.

For example if a movement (goblet squat, back squat, front squat, single leg squat. etc.) is causing pain in the knee or ankle or spine, it is a good idea to block off the ankle with a slant board and see what its effects are on the pain and biomechanical positions. What you are doing here is artificially giving the athlete a greater range of motion in closed-chain dorsiflexion. If this clears the pain, then it would be a good idea to collaborate with a physio, chiro, or athletic trainer to address this range of motion problem that is likely being caused by overactive tissue in the posterior lower leg some or provide guidance on self-mobilization with a roller and static or dynamic stretches can be done as well but being cautions of stepping into other departments areas and operate within your scope of practice. I would never recommend a strength coach to put their hands on an athlete in any circumstance, but especially not to do soft tissue work unless you are a dual practitioner AT, DPT, LMT,DC ect.

Video: Sagittal plane view of a bodyweight messier squat

If a loaded lateral movement (lateral lunge, Messier Squat, etc.) is causing pain in the ankle, knee, or back, then a different protocol would be implemented. The Messier squat brings the ankle into dorsiflexion in a less extreme position than a sagittal plane squat but it brings that ankle into much greater ranges of inversion and eversion than a sagittal plane squat. If pain only occurs with loaded lateral movements, then it is likely not an issue of dorsi and plantar flexion but of inversion and eversion. Taking the side that is experiencing pain and putting the athlete in a greater range of inversion or eversion will either make pain worse or eliminate pain based on which movement their lack of range is in. Using a slant board to put the ankle in a fabricated range of inversion and/or eversion in a similar way to how we used the slant board with a traditional squat pattern to screen the ankle’s involvement will tell us if the ankle needs work on the tissues related to inversion and eversion.

Image: Example of an athlete using a slant board to bias the foot into eversion

Central Back Pain

We can also use back pain as an indicator on either a lateral or traditional squat. Positioning is important. If the athlete is not able to keep the torso vertical, then the pain could be coming from the torso dropping forward in the lower portion of the squat. The reason the torso is falling may be coming from the lack of ankle mobility, so then instead of moving at the ankle the individual will just dump the chest forward to fabricate a lower feeling position. I have seen individuals immediately change biomechanical positions and erase the pain they were experiencing by changing the ankle position with a slant board. I say this to provide context to the next sentence, which is If someone is presenting with this back pain while squatting in a traditional or lateral pattern and the positioning of the movement looks funky, then it is likely a bilateral dysfunction. Meaning you will be able to observe a similar active range of motion on both sides.

Using the Messier Squat for Ankle or Knee Pain

We typically see that pain in the ankle or knee only presents on only one side of the body. While it would be more thorough to evaluate both sides to get a greater context of the individual, it is likely something that is only an issue on one side. I have especially noticed this in return to play for knee/ankle injuries. Everything feels good until they move in the frontal plane and realise lateral movements present pain in the area of concern. Using the Messier squat as a movement screen could be useful for individuals with chronic ankle sprains and/or that experience knee pain with lateral movements. Most of the time, if pain is occurring during a lateral movement, putting the affected side in either inversion or eversion will clear pain and or movement issues.

The way I teach the Messier squat for this function.

Feet

Stay flat to the ground during the entire movement.

Knees

90-100 Degrees of knee flexion to almost full extension.

Hips

Stay low entire time.

Torso/Shoulders

Upright torso position.

Head

Ear in line with shoulder or just slightly in front.

Video: Side view showing the sagittal plane of the Messier Squat

Note: Many allow for excessive movement in the Messier squat by allowing the foot with less load on it to rotate up towards the sky and come off the ground. I find this to be less beneficial for using the movement as an evaluation. Often when this happens, the torso will drop and/or rotate. The Hip will externally rotate, and the range of motion of the more loaded leg will have a slightly greater range of motion. Since I mostly train larger teams, I tend to lean into weight room movements with fewer moving parts to create consistency and to run a smoother session. This allows for consistency of evaluation by standardizing this movement having both feet on the ground.

Note 2: it is important to view the movement from an anterior standpoint and a lateral standpoint at least. Posterior doesn’t seem necessary, but it could be given the specifics of the case.

Video: Frontal Plane view of the Messier Squat

Two ways to implement these pieces of information

- Using a movement screen and addressing any issues is the better option and allows for a more permanent solution. However, it also takes a lot more time and dedication from the athlete and practitioner. Fixing the moment strategy by addressing the restricted tissue and strengthening the weakened tissues will allow the athlete to move without restriction through the required ranges of motion and no longer cause biomechanical faults and or pain.

- The simple and easy approach is to leave the problem unaddressed, but to still get the athletes out of poor movement and or pain. Just continue to use a slant board while doing movements that require ankle mobility that they are deficient in. Although not the ideal solution, it will keep the athlete out of a poor position and pain while in the weight room.

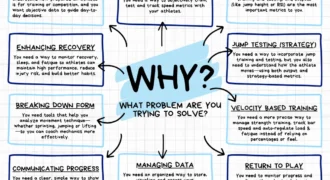

Cheat Sheet

Image: Chart showing what tissue in the lower extremity is likely causing mobility deficits

Final Thoughts

Movement issues can be multifactorial and complicated to understand. I have noticed that many times changing ankle position almost solely resolves someone’s biomechanical faults and resolves the pain they experience with certain movements, but there are other cases where it may reduce the biomechanical glitch or ease the pain without fully fixing either one. This would indicate that there is more than one issue at hand and would warrant further investigation upstream. The other consideration is with athletes that have a young training age or are new to the weight room, I would not be quick to jump to conclusions when using loaded movements as a primary assessment technique as their limited exposure to training will likely leave them less than skilled enough to know where the body should be in time and could allow for some faults that could be coached out of them fairly quickly.

Note: all pictures and videos have been taken with people wearing shoes. This can be fine, especially if it feels very clear that you’re on the right path. It is always better to take the shoe off and see what the foot is doing during these movements.

The post Using the Messier Squat to Address Ankle Dysfunction appeared first on SimpliFaster.