Introduction

Strength and conditioning as a field has grown tremendously in the past 20 years. What started as something that was in a few weight rooms for a few select sports programs has become a staple for almost every collegiate and professional organization, with high schools starting to follow suit. Following that is the work of coaches in the private sector who can preach whichever niche training philosophy/methods to sell to athletes looking to take their abilities to the next level. While a lot of coaches do a great job of getting their athletes training they won’t get elsewhere with principles that are proven, this also brings other coaches who aren’t grounded with knowledge in exercise physiology and look to take advantage of the growing field to make money. This is what I believe is the current “sports specific training” that parents fall victim to and without proper knowledge of what to look for, athlete development can be lost.

The “Specific” Issues with Sports Specific Training

Sports specific training to me, and I assume to many other professionals in the industry, is not only a buzz word to get the attention of parents, but also trying to blend the weight room with attributes of a sports skill to try and get benefits of both in one session. Examples you might see could include:

- Dancing around cones for “footwork.”

- Wearing resistance weights on their limbs performing sports skills

- Performing exercises on bosu balls/unstable surfaces to try and to train balance.

- Using cable machines and bands to mimic movements like baseball throws and volleyball armswings.

These give off the illusion of being helpful to the sport by passing an optics test. Seeming similar enough to the sports skill but having weight room tools attached to it gives the impression of training in the weight room catered to the sport. Parents fall for this trap very easily since they’ve heard of weightlifting being bad for kids and stunting growth since they were younger, and while all of that has been disproven by new research, I will never expect a parent to read up on the matter even if I put it directly in front of them. Even some of the coaches that prescribe these exercises are not totally at fault in my opinion either. While they are misguided, they are wanting to help the athlete improve which is always a good thing and not everyone is putting these programs together to take advantage of athletes and make quick money.

Where the issue really lies with buying into this style of training is the lack of change/progress. When looking into athletic development, a principle I will always follow is that trying to achieve multiple things at once will achieve less than if you put time into them individually. Physical outputs such as strength, speed, power, conditioning etc; and technical proficiency of a sports skill are on very different points of the athletic development spectrum and require their own large amounts of attention and energy devoted to them. Thinking that we can create drills that will get the most benefit for both at once is fools gold and will only lead to losing possible progress.

Let’s consider a hypothetical example of a volleyball athlete working on approaching the net and hitting with weighted wearables on, such as wrist, ankle and vest. This on the outside looking in could look like a great supplement to a players game, and maybe with very small amounts of weight this could have some benefit. But I have seen this implemented only with too much weight to the point where the athletes technique changes as a whole. While this will be hard for the athlete to do and the mindset of “do hard things” is preached over and over in society today, we are not accomplishing anything with this kind of training. The weight attached will have the athlete developing and working with poor technical habits, however, the weight is not nearly heavy enough to get a physiological change and is only a hindrance to the athletes technical work.

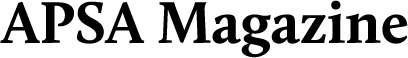

In the book “Game Changer” written by Fergus Connolly, he speaks of the four coactive model that covers four areas of preparation for an athlete and how their development can be trained. Two of these coactives that fit this article are the technical, referring to skill, decision making and execution, and the physical, referring to biodynamics, biomechanics and bioenergetics. These coactives represent a model of not how to look to work them not to be combined, but to coincide. We want athletes to be developed to their highest level and as strength and conditioning coaches, we must be able to maximize the physical coactive to the highest level possible. This model by Connolly I believe is a need for any coach in any sector of sport to read in order to understand where methods belong in the grand scheme of athletic development and is a great key to avoid using inferior training methods. If we look to meld these other elements too far into our methods, we lose sight of what we are trying to accomplish.

Image: 4 Coactive Preparation Model of Athlete Preparation from Connoly, F. and White, P. (2017) “Game Changer: The Art of Sports Science” Victory Belt Publishing

GPP’s Application to Growing Athletes

When an athlete is looking to develop the body physically for their desired sport, they’re probably going to look to do that in the context of their sport of choice. Athletes have availability to the internet and social media more than ever, and they are one search of “training for *insert sport here*” away from doing dances with cones and weight vests weeks. It’s up to us as professionals to provide content to try and set the athletes on the right course of knowledge. Thankfully, knowledge of GPP (general physical preparation) and training methods regarding it have been around for a long time thanks to pioneers of the field like Louie Simmons, Buddy Morris, James Smith and others. If we want to know how to cater to a sport in the weight room first, we have to understand the general application of strength and conditioning and the benefits it has.

In short, GPP is the use of training outside of the sport itself to improve an athlete’s physical base. This article can go into much greater detail of the contents of GPP Training, but in short we want to bring up every physical capacity at a consistent rate through long term training progression and variability. These methods can include, but not limited to:

- Full body resistance training with different tools, movement patterns and planes.

- Speed/agility training with different contextual stimuli.

- Plyometric/jump training through different methods and planes of movement.

- Conditioning with different tools and challenging different energy systems.

When bringing up GPP, I want to put away the idea of the athlete in the context of their sport and focus on the athlete in the context of outputs their body can achieve. Improving these qualities has shown to have not only performance benefits but for health as well. The idea of playing multiple sports to become a better athlete has always been around and has some merit to it, but I believe that it’s more of having different stimuli challenging the body through playing multiple sports increases well rounded physical ability while also fighting overuse injuries. Kids are specializing more in a single sport than ever before, and the weight room can be the key to building GPP and making sure health and performance are steadily improved over time for these athletes.

The weight room can be the key to building GPP and making sure health and performance are steadily improved over time for these athletes, says @PLCstrength

Share on X

How to do “Sport Specific Training” Correctly

It might seem counterintuitive after giving you sections of why I think sports specific training is not the way to go, and then telling you how I do “specialize” in the weight room but hear me out. To me the weight room in all contexts to sport is GPP. Coaches like to plan training in phases that might be labeled GPP, and then an SPP (specific physical preparation) phase follows it with exercises that might look more like the sports range of motion/ contribute to sporting movement outputs. I find it more simple to think of everything the weight room can do as general because when looking at an athlete’s entire training year nothing we can do in the weight room will truly replicate the demands sport will have. Instead of thinking of methods to specialize, we can instead look at organization of volumes of training stimulus to properly cater more to a sport.

Instead of thinking of methods to specialize, we can instead look at organization of volumes of training stimulus to properly cater more to a sport, says @PLCstrength

Share on X

Plan According to Time of Year

Every sport has periods of time designated for sporting procedures. Off-season, pre-season and in-season all have their roles in the sense of the technical coactive. This will be the same for the physical as well. Knowing the flow of sporting practice and competition can allow you to plan the weight room and supplement the sport properly. While this can change for an individual athlete and their specific needs, I’ll refer to a general plan for ease.

Offseason

- Higher volumes with lower intensities. Slowly progresses inversely as time goes on.

- More variety of exercises, implementing new movements with different motor learning challenges.

- Higher levels of conditioning if a lack of sporting practice.

Inseason

- Lower volumes with higher intensities. Higher sport practice will take away weight room volume.

- Less variety. Variety creates mechanical damage and soreness and is best kept for off-season.

- Very little conditioning. Practice and Games should serve as the main form of in-season conditioning.

These outlines are very simple and can have a lot of nuance depending on the coaches preferences and philosophy, but these principles are followed in any good strength and conditioning program. Things also change when there technically is no true off-season. Working a lot with volleyball players year round, I see athletes that play every week year round going from school to club competition, so your training plan will get more complex dealing with situations such as that. Regardless, finding proper volumes of exercises to do at certain periods throughout the year for an athlete will allow them to be in optimal shape at the correct time of year. Below is an example of a general template I have used for the planning of a year round volleyball athlete.

Image: Sample offseason training guide for a volleyball team or athlete. Want a guide for Club Season and Competitive Season? Enter your email at the bottom to get both as a PDF

Train Physical Qualities that Lend to Their Skills

While we want all qualities to increase within the weight room to build the well rounded base of GPP, finding outputs that are KPI’s more specific to the sport and honing in on them when appropriate is a good way to assure athletes are peaked for their sport. While I am a believer that everything should be trained concurrently throughout the year, higher volumes/intensity of the exercises we believe are going to cause the biggest rise in performance can provide aid to sports performance. This can be done by doing a needs analysis of the sport/team personally and working backwards from what we want the athletes to have on game day. This is where coaching creativity can come in depending on the sport and how nuanced you get with the positions within the sport as well.

For example, sports like golf and Tennis will look to increase rotational power as the main scoring skill of the sport involves rotation. Golf will not have displacement qualities like speed of change of direction assessed as a direct KPI since the sport does not involve them, however tennis will look to improve these qualities to enhance movement to better react and get to the ball. This doesn’t mean golfers should never sprint or work a change of direction, as these will promote better overall athleticism and health, but when we are closer to competition periods we have to allocate our time and training volume to what truly matters within the sport. And if we compare Tennis with another rotational sport like baseball/softball, both will look to improve rotational abilities, but baseball looks to dominate more of its movement on linear speed and tennis more so with change of direction. Differences in these athletes programs when it comes to more “in-season” programming can be a change of volume prescription.

A hypothetical split for each team could be:

Image: Chart showing how different sports can differentiate their training by training the same things but with different volumes

Assuming that the offseason plan has built up athletes for these volumes, Tennis has a lot more total mileage in their sport then baseball/softball but allocating the volumes to where they’re primarily needed would be your best bet. So baseball/softball I would do most of my volume in linear speed and Tennis having it mostly in COD. Golf has a split between them with less overall yards then both, but these are just for general outputs instead of specificity. You can come up with different ways to split and you might disagree with the volumes I put, but keep in mind this was just an example of the thought process so don’t worry about the numbers shown. Every team is working these GPP training methods and aspects, but getting their own “sports specific” split up of volumes.

When thinking about the weight room, it comes down to how much strength is a true KPI in the sport itself. Everyone loves the saying “there are no barbells on the field” to deter athletes from obsessing over the weight room, but if we start to discredit ourselves we devalue what we can do with the tools we have. There are certainly athletes like soccer players and cross country runners who more than likely won’t see a direct performance increase from improving weight room numbers, but denying the benefits strength training has on overall health and the transfer it has on other KPI’s like speed and power leaves so many gains on the table. And for athletes like football offensive linemen and wrestlers, try and tell me that improving upper and lower body barbell strength won’t help them with what they have to accomplish in their sport. If you believe strength is pushing the envelope, keep it developing with the proper principles of periodization. If it’s not a KPI to you for the sport, keep it in for a basis of health more. The weight room is another piece of the puzzle, and thankfully we have a lot of different pieces that can fit our athletes.

Image: Volleyball athletes performing half-kneeling rows, trap bar deadlifts, and approach jumps on a vertec

Catering to the Sports Common Injuries

Probably the easiest to understand, If you know a sport has a site of injury that happens the most, planning to train those areas is a must. Building up muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fascia through resistance training can be the best way to keep the body healthy in the fast chaotic nature of sport. While a well rounded profile of resistance training will always cover a lot of bases, thinking of the small things sports will have in comparison (neck work for concussions, ankle training for common sprains, etc) can be the extra that can save an athlete on a play. With the statistics we have now on the most common injuries of every sport, finding accessory work that can build up these areas resiliency is an incredible way to work for “sports specific” injury needs.

A Specific Ending

We might never see a time where coaches who preach their “sport specific” training programs stop taking hard earned money from families for their athletes to waste their time with no results to show. All we can do is provide an outlet of good training with real results to combat it. What we can do to truly help is offer a platter of GPP training with a “sports specific” spice to keep the athletes healthy and improve their ability to play the sport they love. If you follow these principles, I have no doubt you can create training that can truly put athletes on the correct and “specific” path.

And don’t forget, if you want a PDF of Guides for Offseason, Club Season, and Competitive Season, enter your email below to download your copy now.

References

Connoly, F. and White, P. (2017) “Game Changer: The Art of Sports Science” Victory Belt Publishing

The post How to do “Sports Specific” Training the Right Way appeared first on SimpliFaster.