Introduction

The Cold War was an era marked by bigger, better, badder everything. One country made a new rocket, the other country one upped them. It was constant one upping, back and forth, racing to the top. More complicated, more energy, and more resources needed.

As I sat in my office in 2024, I felt the same weight, only from weight room equipment and technology companies. It now seems that if you don’t have the latest and greatest everything, you’re falling behind the arms race. Every week a professional team, university, private facility, or even high school puts out a sizzle reel with all of the hottest new tech they have and the thousands of rows of data each one captures per repetition. Not to mention the thousands of dollars price tags upfront and high priced yearly subscriptions for their software.

Enter OVR Performance. Their breakthrough innovation was a call back to simplicity and affordability. Enough units could be reasonably purchased to outfit a facility and simplify things for coaches and drive intent for an entire team of athletes. Technology in the weight room isn’t going away. But sometimes I want dummy proof for my athletes and to capture only the data that actually drives and informs training decisions. Simple feedback loops for the athletes and me as a coach.

I have now implemented OVR Jump (and Velocity) into my training for a year between an in season and off season. I could not be happier with the results, the feedback from athletes, or the ideas I have for year two.

Getting to Know OVR Performance

OVR Performance, which recently added a laser timing system, includes OVR Jump for tracking various jumps and ground contact times (GCT) and OVR Velocity for tracking bar speed (and more if you get creative).

This article will focus on my experience with OVR Jump over the past year and how I used it with two men’s and one women’s college hockey teams. Liberty University Hockey competes in the ACHA, not the NCAA, which enables us to have multiple hockey teams at the collegiate level.

OVR Jump is a laser based jump system. You may measure vertical jump, RSI, or ground contact. With its built-in display and light weight units, the Jump is fool proof and very portable. This is ideal for the way I lay out workouts and the various jumps I track, in various parts of my weight room, in various blocks of my workouts. Other bulky devices simply do not transport as quickly mid workout.

Video 1. OVR Jump unit being brought from the hallway into the weight room.

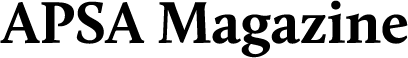

OVR Jump puts a tool in a coaches hand that allows them to easily program exercises along the spectrum of the Force-Velocity Curve. Looking below, here is an offseason workout copied and pasted from TeamBuildr. I have highlighted where and how OVR Jump was used on this day:

Image 1. Summer workout utilizing OVR. Units started in the hallway to measure GCT of hurdles during speed drills block. Then brought to the weight room for B block. Used to measure jump height of weighted and unweighted vertical jump as well as GCT of depth jump variation. Hurdles and vertical jumps were recorded.

Image 1. Summer workout utilizing OVR. Units started in the hallway to measure GCT of hurdles during speed drills block. Then brought to the weight room for B block. Used to measure jump height of weighted and unweighted vertical jump as well as GCT of depth jump variation. Hurdles and vertical jumps were recorded.

With its price point, I could purchase three OVR Jumps versus one of a competing jump system. And the best part? I buy it once, use it forever. There is no yearly cloud subscription to use the unit or their app.

A quick note on OVR Velocity. I personally have never used a camera based velocity unit, such as Perch. I have used accelerometers, but all in all I love attaching a tether to a bar. It’s the simplest, least complicated in my opinion. OVR provides velocity, power, and a few other metrics like time to peak velocity. Again, I understand the benefit of many different metrics, but day to day these are the ones I use most, so I am more than happy to not pay for fluff that I do not use.

How I Used OVR Jump in a Team Setting

As shown in Image 1, I use OVR to track different jumps, in different parts of my facility, in different blocks of my workouts. I have measured hands on hips vertical jumps, dumbbell jumps, seated dumbbell jumps, RSI off a box, depth jump GCT, single leg depth jumps, and of course hurdle hops.

Video 2. Example of jump and measurement variations OVR Jump is capable of.

For hurdle hops, I copied Coach Michael Fahey’s recommendations on using them between hurdles to measure GCT, aiming for a contact of 0.15 seconds or faster. I used three OVR Jump units and set up five hurdles and placed the units on the last three. Athletes would jump through, a teammate would read their slowest GCT and that would get recorded. This flow worked very well. It created high accountability as GCTs were read aloud and recorded on a clip board for everyone to see.

Video 3. Team using OVR Jump in between hurdles to measure GCT.

As the weeks progressed, based off of GCT’s I split the team into two groups, one performing hurdles at the start of the workout and one at the end. For example, Group 1 would be using 5 foot spaced hurdles and Group 2 would be using 6 foot spaced hurdles. The two groups kept the flow of the workout moving and allowed me mid workout to lengthen out the hurdles and near the end move the OVR units back out to the hallway.

The best part of OVR Jump in a team setting is the simplicity. I love that the display is built in and does not require an app to run the units and capture data. There are no tablets to make sure they are synced and another thing to charge. This cuts down on set up time for coaches who don’t have an army of interns. OVR Jump is a swiss army knife for a strength and conditioning coach that wants exact measurements, high intent, and consistent work flow block to block to block of a workout.

The best part of OVR Jump in a team setting is the simplicity. I love that the display is built in and does not require an app to run the units and capture data, says @coachchriskerr

Share on X

Athlete Feedback, Data, and Results

There is nothing more satisfying as a coach than hearing, “Oh I get it now.” And this was a common occurrence this past year as OVR Jump made words like elastic and stiff make sense to athletes. Suddenly exercises like altitude drops and spring ankle made more sense to them.

For years I’ve wanted a way to measure and display stiffness, horizontally. How are athletes interacting with the ground? And are the vertically oriented weight room exercises translating to horizontally oriented stiffness? Using OVR Jump to measure hurdle GCT did that.

In addition to hurdles hops, when a single leg depth jump was added, that was an eye opener for me and the athletes. The deformation of the body was incredible to see and the GCTs were the feedback the athletes needed to understand total body stiffness. Again, it is very satisfying to hear, “Oh I get it now” as it relates to elasticity and stiffness.

There is nothing more satisfying as a coach than hearing, “Oh I get it now.” And this was a common occurrence this past year as OVR Jump made words like elastic and stiff make sense to athletes, says @coachchriskerr

Share on X

Video 4. Single leg depth jumps, landing to a box, keeping GCT under 0.2 seconds.

Looking at data from just one of my men’s teams, they had great results in season. On average, the team saw a 10% drop in GCTs across the year. The highest change being 30% faster, with one player actually getting slower by 15%. Interesting to see who did and who did not improve and reverse engineer why.

All of these results come with asterisks’ however. The biggest reason is the game is constantly changing. Once athletes consistently approached 0.15 seconds of GCT, their hurdle distance was moved out 1 foot. So their week 2 and 3 GCT records were on hurdles 4 feet apart. Their records before Nationals were on hurdles 6 or 7 feet apart. So not only was their improvement for most athletes, but they were faster off the ground while jumping further distances between hurdles!

Figure 1. Men’s hockey team percent improvements in season hurdle hop GCT’s. Each workout, slowest GCT of 3 sets recorded. Slowest time from Week 2 or 3 used as baseline. Pre Nationals was last or second to last workout before the National Tournament.

Figure 2. Men’s hockey team single day of slowest GCT across 3 sets recorded.

A final noteworthy piece of data is that the 2024-2025 season marked the most athletes sprinting under 1.90 seconds on the 1080 Sprint for 10 meters, with 1 kilogram of resistance. I have been using a 1080 Sprint since the 2020-2021 hockey season. And the only thing that changed this year compared to last year and most others was the addition of OVR Jump. The data below speaks for itself.

Figure 3. Historical data revealing the most athletes accomplishing a 10m sprint in under 1.90 seconds on a 1080 Sprint. Of the 8, 6 are new to the list. 1 of which was a freshman.

Now, are there other tools out there that measure jump height, RSI, and ground contact time? Yes. But again, my argument is the portability and price point is a no brainer. I take OVR Jump from a hallway, to the weight room, back to the hallway without blinking. I toggle between ground contact and vertical jump settings in 10 seconds. It’s clear, concise, and I may outfit my weight room to accommodate a team without spending my entire budget.

Troubleshooting

Now, like anything, there is always trouble shooting. Some of the greatest sprints I have ever seen in my life never got recorded. We’ve all been in a situation like this and OVR Jump is no different.

The biggest troubleshooting to get around is jumping and landing outside of the laser field. This happens every now and then with hurdles, especially. The athlete starts a little off and then continues through the hurdles. Similarly in the weight room with RSI or depth jumps. Missing the laser field will cause a jump to not be recorded. In addition, the laser field is determined by how far apart the two units are. So if you’re in a narrow hallway jumping through hurdles (such as myself), athletes may miss a laser.

The OVR engineers did create a work around, in which two units may be linked together. The link creates a broader field for the laser and is only possible to miss if something goes really wrong. My fix was a piece of tape for athletes to aim for, ensuring they’ll land in the laser field, or place the units on a line during set up. This gives a visual cue for the athlete to hit.

Image 2. Tape and a line used as visual cues for athletes to land on.

Aside from missing the laser, the battery needs to be charged. In one year, that is all the troubleshooting I have ever faced.

Year Two

Year two will be marked by individualized jumps or ground contacts based off of Force-Velocity Profile data from my 1080 Sprint. This will look like individualized GCTs, distances, and heights for hurdles and specific depth jump goals.

For example, a Force-Velocity Profile shows poor acceleration. I want to utilize OVR Jump to achieve more force. I would have hurdles closer together and taller so this athlete trains to deal with more force. And in the weight room they would perform depth jumps for height, which would also create more force versus a depth jump focused on the fastest possible GCT.

Next, this summer I experimented a lot with single leg depth jumps and this will expand into single leg hurdles. When performing the single leg depth jumps it was obvious and apparent the strongest and fastest athletes hit the fastest GCTs and the weaker and slower athletes got stuck on the ground. It was even more apparent as I pushed the step off height from eight to twelve inches. The slower athletes simply could not handle the force and oftentimes could not make it up onto the twenty inch box.

Video 7. Single leg depth jumps, landing to a box, keeping GCT under 0.2 seconds.

Combining more tools, the 1080 Sprint displays left/right asymmetries. Here is a visual of one leg producing more power than another. With the OVR Jump I may be able to identify these asymmetries as well during a single leg hurdle hop. Or when I notice these on the 1080, I will have more tools to train with. And this concept may be applied without a 1080 Sprint. Simply measure single leg exercises and note any asymmetries.

Image 3. Power asymmetry between legs, as displayed by the step graph on a 1080 Sprint. The red and black line are two different sprint repetitions, representing this was not a fluke thing. Once identified, OVR Jump may be used to train this asymmetry and restore balance and be another tool in the tools box.

Some final thoughts for year two also include using OVR on the ice to measure first step GCT. In the sport of hockey, most accelerations start with a crossover. And when that first skate hits the ice, ideally only one-third of the skate blade hits the ice. It is the same concept in sprinting, you want limited heel drop in your first step. I’d like to find an ideal ground contact time for this first step on ice.

Image 4. Women’s player skating away, initiated with a crossover start. Notice the elevated “heel” or skate blade during contact with the ice, similarly to sprinting off ice. The goal is to use OVR Jump to assess these GCTs on ice.

And lastly, now that I know the accuracy and ease of use with OVR Jump going through hurdles, I want to see if there are good readiness indications that may come from it. I would get a baseline of sorts and assess when a player or team is well below their norms for GCT and make the necessary adjustments. Is what it is, athletes may cheat a vertical jump. We’ve all seen the videos with huge knee bends upon landing. But with 3 OVR Jumps to hurdle through, I trust that measurement.

Here’s to year two!

For those wondering, what were the results of the teams using OVR Velocity and Jump at the end of the year? One men’s team achieved a number one ranking in the country, losing in Game 3 of National Tournament Pool Play which would have sent them to the semi finals. Another men’s team lost in the semi finals to the eventual champions. The women’s team won Nationals in double overtime. Number 1 ranked in the regular season, top 4, and National Champions. Not too bad.

Image 5. Liberty Women’s D1 ACHA Hockey Team. 2024-2025 National Champions.

The post My First Year With OVR Jump appeared first on SimpliFaster.